Introduction

Depression is a prevalent and debilitating condition that affects millions of individuals across the United States. Primary care settings serve as the frontline for managing a broad spectrum of health problems, including mental disorders. Consequently, most patients receive treatment for depression directly from their primary care provider (PCP). Thus, PCPs play a crucial role in the initial identification, management, and follow-up of depressive disorders.

Most patients with depression can be effectively managed in these settings using evidence-based, first-line interventions like antidepressant medication and psychotherapy. However, some patients may not respond adequately to first-line treatments, necessitating consideration of alternative options. It is essential to recognize when to make this decision and to understand the array of possible interventions. This article describes neuromodulation co-management in primary care, in a manner similar to collaborative care, and specifically focuses on Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) and Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT). Guidance on referring patients to specialized care facilities is provided.

Neuromodulation

First-line treatments for depression typically include talk therapy like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and antidepressant medications, such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). While these treatments are generally well-tolerated and effective for many, approximately one-third of patients may not achieve sufficient symptom relief or may experience intolerable side effects limiting their usefulness. For these individuals, alternative approaches like neuromodulation may offer important benefits.

Neuromodulation is an emerging treatment area comprising various interventions that modulate neural activity in the brain to improve mood and other neuropsychiatric symptoms. These interventions are broadly categorized into invasive and non-invasive treatments, with most being low risk when used in the appropriately evaluated and medically optimized patient.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

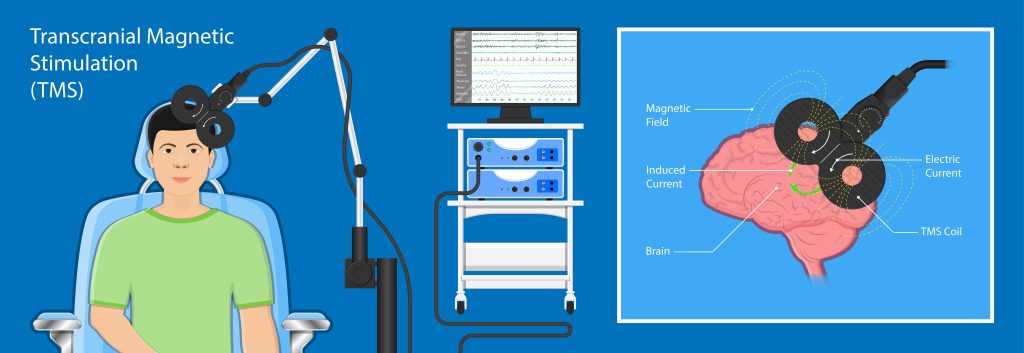

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) involves delivering magnetic pulses to specific brain regions to modulate neural activity. This non-invasive procedure is brief (lasting about 20 minutes per session), performed on an outpatient basis, and is generally well-tolerated by patients. TMS is used adjunctively, meaning that patients often continue medications or talk therapy or both. Common side effects, such as headaches or scalp soreness, are relatively minor. The major risk is for seizure, which is mitigated through careful patient screening and strict adherence to treatment protocols.

TMS is FDA-approved for several indications, including Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD), Anxious Depression, Late-life Depression (up to age 86), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and smoking cessation. TMS is covered by most insurance plans, although prior authorization is required, and not all indications may be covered. Importantly, TMS usually does not involve additional medical work-up for most patients. More information about TMS can be found here: https://www.uwmedicine.org/practitioner-resources/center-behavioral-health-learning/neuromodulation

TMS and Primary Care

PCPs can effectively co-manage patients undergoing TMS in collaboration with a CfN psychiatrist or other mental health specialist, if needed and similar to collaborative care. Established protocols for behavioral emergencies ensure outpatient safety, while adjunctive treatments, such as medications, may be recommended to optimize outcomes. Familiarity with combination antidepressant approaches is helpful for PCPs involved in co-managing these cases, especially when the acute series of TMS treatments is completed and the focus of care turns to relapse prevention.

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) involves administering electrical energy to the brain to stimulate neuroplastic processes resulting in modulation of neural activity. The procedure is done while the patient is under brief general anesthesia. ECT is a highly effective treatment for major depression, whether associated with unipolar or bipolar disorder or complicated by psychosis or catatonia, or when a rapid response is needed due to the severity of the psychiatric or medical condition. Most patients can receive ECT on an outpatient basis, though those with more severe depression may require inpatient management.

Although there are no absolute contraindications to ECT, there may be relative contraindications necessitating thorough evaluation and discussion to appropriately risk-stratify and medically optimize the patient. Insurance, including Medicare and Medicaid, generally covers ECT, though managed care plans will often require prior approval.

ECT and Primary Care

Patients undergoing ECT usually require co-management with a psychiatrist or other behavioral health specialist due to the severity of their illness, not because of ECT. The main role of the PCP in the patient undergoing ECT involves conducting a pre-operative evaluation for the procedure since brief general anesthesia will be used. After the initial phase of ECT, the focus shifts to relapse prevention over the following 6-12 months. Strategies for relapse prevention may include combination pharmacotherapy, continued ECT but at reduced frequency, psychotherapy, or other neuromodulation techniques. PCPs should be comfortable collaborating with behavioral health specialists during this phase to identify early relapse.

Conclusion

Managing depression in primary care settings is both a challenging and rewarding endeavor. While many patients respond well to first-line treatments like CBT and antidepressant medications, a significant proportion may require other interventions. Neuromodulation therapies, such as TMS and ECT, offer alternatives for patients who do not respond adequately to initial treatments. By leveraging collaborative care models and co-managing with specialists, primary care providers can continue to help patients and improve outcomes. Referring patients for neuromodulation consultation ensures their patients receive the most appropriate and effective intervention, thereby improving their overall quality of life.

Referring to the UW Medicine Garvey Institute Center for Neuromodulation

The Garvey Institute Center for Neuromodulation at UWMC-Northwest provides a comprehensive suite of neuromodulation treatments within a collaborative care framework, ensuring patients receive holistic and coordinated care. When considering a referral for neuromodulation consultation, primary care providers can access information on the CfN website. The referral process entails providing a reason for referral (e.g., diagnosis), a clinical synopsis of the case, details of current treatments tried, and, if known, the requested intervention.

What to Expect from the Initial Consultation

Comprehensive Review: The initial consultation at CfN provides a thorough review of the patient’s current and relevant medical and psychiatric history and documents a comprehensive mental status and behavioral exam.

Identifying the Best Intervention: The CfN consultant will determine whether neuromodulation is indicated, and if so, the most appropriate neuromodulation intervention to address the patient’s diagnosis.

Explaining the Procedure: The specialist explains the chosen procedure in detail, ensuring the patient understands and consents to the proposed treatment.

Preparation Steps: The consultation includes outlining the necessary steps to prepare for the procedure.

Feedback to the Referring Clinician: Finally, the specialist provides detailed feedback to the referring clinician, including findings, preparation or treatment plans, and follow-up recommendations.

Author

Dr. Espinoza is the medical director of the Garvey Institute Center for Neuromodulation located at the Center for Behavioral Health and Learning. He specializes in behavioral health, psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. He holds certifications in electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

Related Resource

Dr. Espinoza put together this presentation about the Center for Neuromodulation where his team provides state of the art neuromodulation and interventional psychiatry treatments including: Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS and dTMS).